Our palms are filled with lines of various kinds—sharp and clear, light and deep, small, repeated, and crossed. To an ordinary eye, they appear as an incomprehensible web. To a palmist, they form a code: a pattern to be read, analysed, and interpreted to reveal personality, trace the past, describe the present, and foresee the future. Each palm is a unique map, a mark of identity.

Hence, the thumbprint is used to sign property contracts, rental agreements, or, in cases of illiteracy, official documents such as passports, national identity cards, or driving licences. Signatures are another form of identification. They are used to open bank accounts, draw cheques, or apply for jobs. One signs a greeting card just as readily as a secret file.

For artists, signatures carry special meaning: they appear on paintings, beneath prints, embedded in bronzes, or behind canvases, often accompanied by a date or year, testifying to authorship and presence. Yet many artists, from the ancient to the contemporary, have chosen not to sign their work at all—perhaps in agreement with Robert Rauschenberg, who once remarked that a signature is merely the final layer of an image.

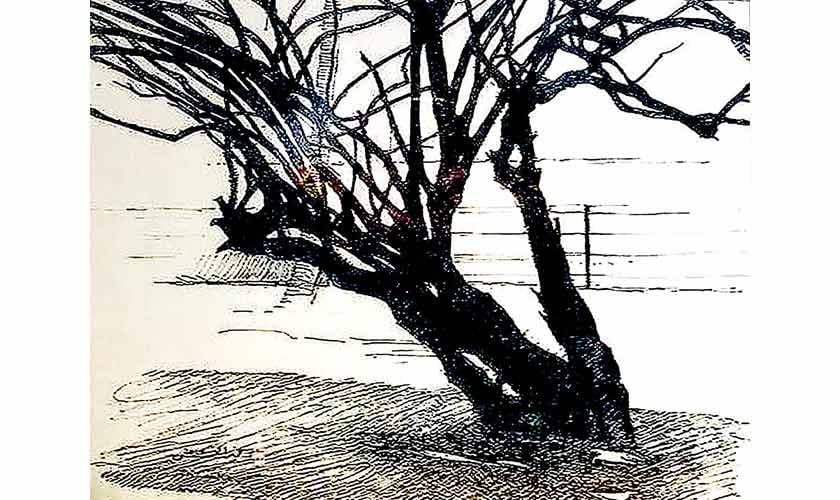

For most people, the first stage of an artwork is a sketch. It is later developed or enlarged into a more complex piece. For others, drawing is an independent creation. Whether a step towards a larger project or a self-contained entity, drawing offers freedom unmatched by what is usually regarded as the resolved work. It allows the artist to observe, experiment, exploit, and diverge—to think visually without constraint.

This freedom of approach is evident in Ijaz ul Hassan’s *Sketchbook: An Eye for the Familiar & the Exquisite.* Edited by Sadia Pasha Kamran and featuring an exclusive essay by Rahat Naveed Masud, the book has been published by Dr Musarrat Hasan.

The volume is significant not only for understanding the process of an artist who has worked for more than six decades, but also for exploring how an artist responds to external stimuli, shifting contexts, environments, and encounters that shape creative expression. The essays by Kamran and Masud provide a backdrop that is both contextual and historical, but it is the excerpts from the artist’s own writings—drawn from various publications and placed alongside his drawings—that offer the deepest insight into his aesthetics, shaped by recurring yet diverse motifs.

The book reads like a tome of pictorial diaries, long kept in closets until Dr Musarrat Hasan, a close collaborator, chose to bring them to light. In his foreword, Ijaz ul Hassan confirms:

> “The sketches compiled in this book are the outcome of travels across the world with Musarrat.”

An original artwork—whether two-dimensional, sculptural, digital, installation-based, or time-bound—inevitably becomes a flattened image when printed in a book, reduced to a uniform dimension and surface. Yet, to truly engage with Ijaz ul Hassan’s drawings, one must consider their original format.

Dr Musarrat Hasan’s contribution in preserving, cataloguing, and recalling the physical and contextual backgrounds of these works is immense. With few exceptions, all were made in small sketchbooks the artist carried with him on his travels. Dr Hasan also reveals that, during his teaching years at the National College of Arts, Ijaz ul Hassan would advise his students always to keep a sketchbook at hand—a principle reflected in his own practice.

For him, drawing was not merely an act of depiction but of perception: he believed that one truly begins to see only when one draws. No wonder these travelogues now appear as the imprint of an artist’s hand—the outcome of his observations, a documentation of his thoughts, and a recollection of his many trips and adventures.

These memories are catalogued by location, subject matter, and genre, rather than in chronological order, thereby preserving the spontaneity evident in the drawings themselves—an immediacy that reflects how the artist looked at and inscribed the world around him.

The components of that world are varied: flora and fauna, human figures, heritage sites, buildings, cities, landscapes, art-historical references, and instances of political commentary. The collection also includes his preparatory drawings for mosaics and murals, a visual response to the Taliban’s attack on the APS children, quick sketches of unknown passengers at airports, portraits of family and close friends, and studies of ordinary objects, often annotated with intimate or humorous remarks.

In one drawing, dated March 8, 2015, Hassan sketched a few bananas with the wry caption, “A bunch of miserable bananas,” recalling Pablo Neruda’s *Odes to Common Things*. Another, depicting Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan mid-performance, bears the line, “Nusrat Fateh executing a passage with full-throated passion.”

The lines that record the visible world and those that express thought through language are, in essence, intertwined.

There are drawings of trees and flowers; his prison cell during Zia’s military dictatorship; views of Murree and Nathia Gali; glimpses of the Mediterranean, Italy, and the United States; as well as sketches from Rio de Janeiro, including the distinctive silhouette of Christ the Redeemer atop Mount Corcovado.

Among the most striking works in this collection are rapid depictions of the Pyramids, the outline of the Sphinx, and the portrait of a mummified Ramses II resting in his coffin. From the boats of Venice and Sri Lanka to the minarets of mosques and church towers, from the rocks of Afghanistan to the Isles of Scilly, and from the intricate details of a few leaves to the expanse of a garden, the artist’s inquiring gaze remains unyielding.

Perhaps one key element lies in a seemingly minor detail: his choice of small notebooks having blank pages on which to record his observations in pen and ink. Although the publication includes a few larger works and pencil drawings, the majority of reproductions are taken from the compact sketchbooks the artist carried wherever he went.

Making drawings or sketches is a common practice among artists across disciplines, yet Ijaz ul Hassan’s relationship with his medium adds another dimension to the work on paper. In addition to being a painter, Hassan is a leading writer on art and culture, the author of *Painting in Pakistan* (1991), one of the key texts on the country’s modern art, as well as numerous essays in catalogues and journals.

An avid reader who studied literature at Cambridge, his relationship with pen and paper extends beyond that of an image-maker who merely transcribes the visible world onto a surface, whether paper, canvas, stone, or any other material.

The difference lies in the act of writing itself. When drawing from nature or one’s surroundings, the artist is immediately engaged with a tangible subject—one that may shift or evolve during the process, yet maintains a kind of fidelity from the outset. Writing, by contrast, is a plunge into an undefined terrain. Ideas drift in the mind, and the act of writing becomes an attempt to translate them into words. It is, in essence, a quest to capture the unknown—a pursuit that continues until the text takes form or reaches its end.

When one examines the drawings gathered in this book, one realises that the artist’s hand never changes, whether he is capturing the quick likeness of a parrot, a branch in bloom, a peach, the profile of his wife, or the form of a sailboat. The hand that shapes his handwriting and signatures also guides these marks.

The lines that record the visible world and those that express thought through language are, in essence, intertwined—confirming that his immediate response to, in Laura Cummings’ phrase, everything he experiences, from the quotidian to the momentous, may differ in medium or form, yet remains unified in spirit.

The content and form of these drawings are not unlike the first draft of an author’s manuscript, from a time before the computer era. They are not displays of the artist’s technical prowess, nor were they intended as exhibition pieces. (Indeed, many were salvaged, cleaned, and separated from old, deteriorating boxes by Dr Musarrat Hasan.) Instead, they serve as records of how a remarkable mind finds new angles, details, and pleasures in objects both grand and mundane, familiar and strange, static and shifting—all through the medium of drawing.

Dr Hasan recalls travelling with Ijaz ul Hassan in the winter of 1965, driving from the United Kingdom to Pakistan. During that 45-day journey, she loaded a 24-exposure roll of film into their camera; only three photographs were taken.

https://www.thenews.com.pk/tns/detail/1350005-a-life-in-lines