**Melancholy Wedgwood**

*By Iris Moon*

*The MIT Press, 248 Pages*

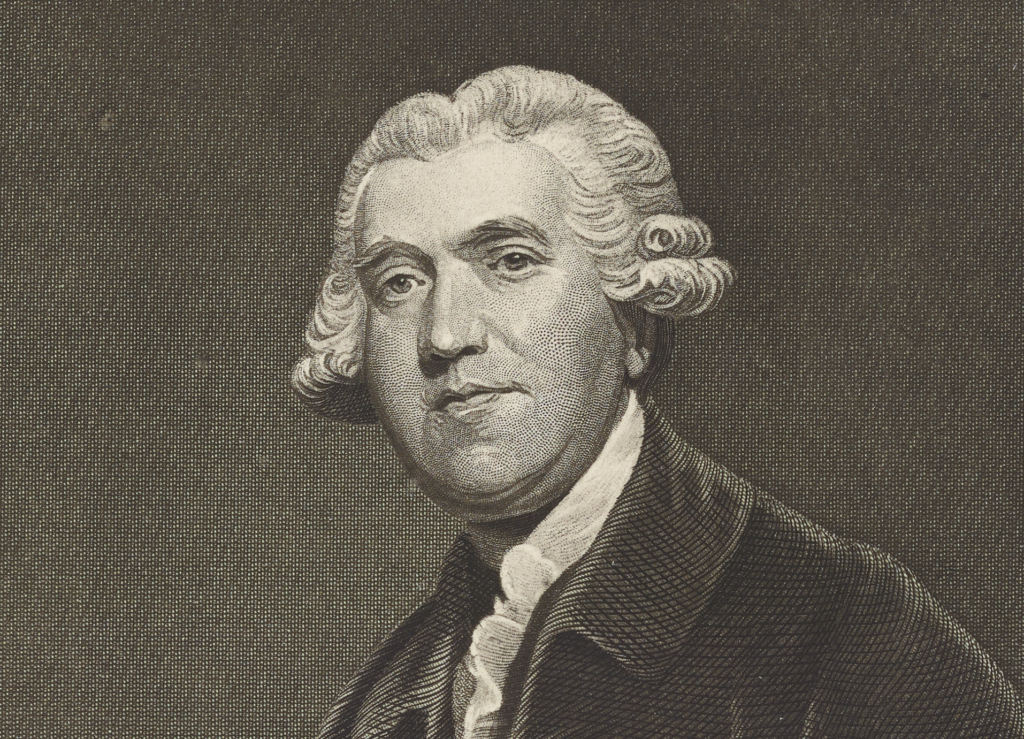

Josiah Wedgwood (1730-95), renowned for his ceramics, created a neoclassical body of work that catered to a commodity culture eager for new pottery and stoneware. His creations bore the look of antiquity even as England’s industrial output accelerated and the very meaning of labor transformed within the factory — a hub of entrepreneurial innovation.

Iris Moon calls her book an “experimental biography.” She deliberately avoids a chronological narrative, which she believes only serves to enhance the mythology of progress associated with the Industrial Revolution. This era, in her view, left behind mountains of wasted materials and lives amid the dynamic of capitalists like Wedgwood, who were determined to invent at any cost—to themselves, their families, and their employees. Their goal was to craft useful and often beautiful objects that glorified households and symbolized the rise of modern business, a rise deeply intertwined with the expansion of empire.

Moon focuses on a biographical fact often mentioned but seldom examined in Wedgwood’s biographies: after he lost a leg, he could no longer sit at the pottery wheel. The amputation, though grievous, relieved him of painful suffering. He recovered well but rarely spoke of his disability, and no images from his native country ever depict him with it. If Wedgwood suffered from melancholy, no biographer has definitively established this.

Yet that does not deter Moon. She notes that melancholy has long been part of the fabric of English life, dating back to Robert Burton’s *Anatomy of Melancholy* (1621). To understand how Burton inspired Moon to offer a fresh, contrarian view of Wedgwood’s life and work, the full title of Burton’s masterpiece is worth citing:

*”What it is: With all the kinds, Causes, Symptomes, Prognostickes, and Several Cures of it. In Three Main Partitions with their several Sections, Members, and Subsections. Philosophically, Medicinally, Historically, Opened and Cut Up.”*

What Burton does for melancholy, Moon does for Wedgwood. She suggests that losing a limb exposed him to a fragmented, dismembered world—one that he sought to reunite through the numerous vases, urns, and vessels shaped by countless failed experiments fired in the intense heat of his factory. Moon even found the rubble of these experiments on a recent visit to England.

Essentially, she argues that Wedgwood’s relentless efforts to reconstitute the classical world in ceramic form parallel, if not stem from, his experience of bodily loss. Crafting ceramic figures was a means of reconstructing himself. Through inventing industrial processes that, despite continual failures, culminated in the discovery of his prized pale blue jasperware—coveted to this day for a color purity rivaled only by the stars—Wedgwood achieved a form of personal and artistic rebirth.

Reading Moon’s interpretation of what Wedgwood’s works signify often reveals meanings far beyond their original intent. It is a philosophical, historical, and medical operation reminiscent of Burton’s own, which dissects and opens up a primal response to melancholy beneath the glossy patina of Wedgwood’s prized pottery.

Wedgwood was a man of tremendous energy who never seemed to pause and reflect on the origins of his manic activity. Moon takes up that task for him—slowing down the manufacturing process, turning Wedgwood over in her mind repeatedly, and uncovering new meanings in old objects or in new objects fashioned to look old.

Biographers often consider their subject’s children to evaluate the legacy left for posterity. In Wedgwood’s case, none of his children showed much interest in their inheritance or managed to sustain the founder’s business. An especially melancholy figure among them was Wedgwood’s son, Tom, who was sickly from birth and never regained his health.

Tom’s story is a poignant coda to the Wedgwood generation. Unlike his father, who staved off despair through incessant labor, Tom had time to contemplate his ailments. He possessed the intelligence to nearly invent photography before Henry Fox Talbot but failed to bring his experiments to the point of scientific proof. His curious story adds a layer of tragic reflection on the costs of the Wedgwood legacy—a generation with too much time on its hands.

*Mr. Rollyson is the author of* *A Higher Form of Cannibalism? Adventures in the Art and Politics of Biography.*

https://www.nysun.com/article/josiah-wedgwood-and-the-melancholy-of-mechanized-perfection