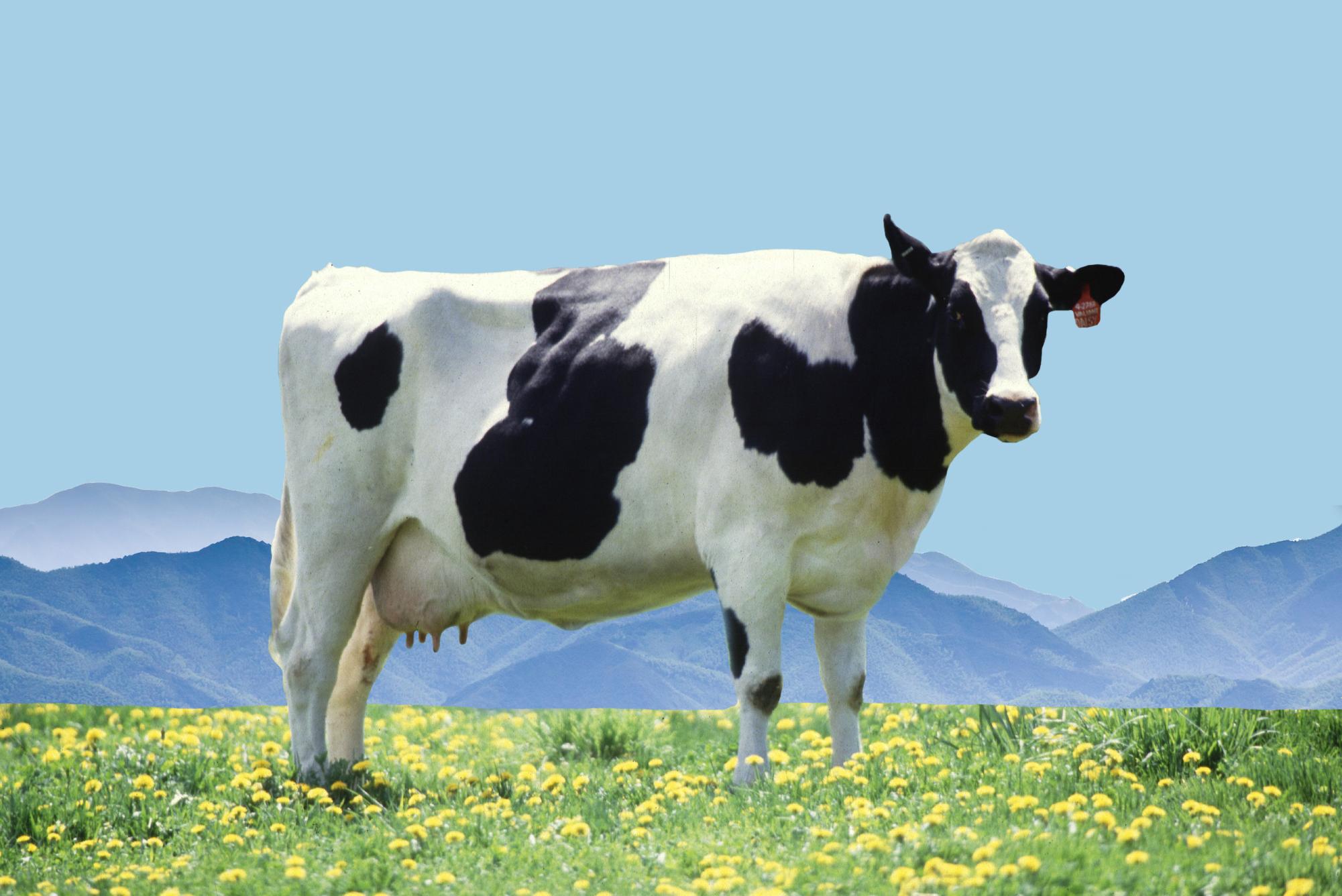

How do we contend with being shaped by where we’re from, especially when we’re too ashamed to accept it? I’ve always lived close to my family, two hours from Campbell County, a county home to the small town at the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains where my mom grew up. It was where her parents grew up too, and their parents before them. My great-great-grandparents, the Pools, moved from Brookneil, Va. to Concord Va. after the Great Depression and made their money growing tobacco and raising cattle. They bought a couple dozen acres after sharecropping for a couple years in town, and built a little farmhouse on their newly acquired land. Now, it’s inhabited by Scott, my grandmother’s cousin. They don’t talk-my grandmother voted for Donald Trump: a hard line, full stop. A dealbreaker for Scott. For me though, it’s more complex. My grandparents were always around in my childhood. They’d come stay with my mom while my dad was at work to help with my newborn sister and keep a 4-year-old me entertained. I have fond memories of tussling with my grandfather, who had to be told to play more gently with me. He often forgot I was a little girl and not an older boy, even though that’s how I’ve always acted. When my sister was older, we’d have sleepovers at my grandparents’ quaint one-story house. I remember going down to the basement to rummage through old baseball cards and antique dolls. It’s just a bit bigger than a double wide, the house where my mother grew up. A couple hundred yards from the house where her grandmother lived and died. I’ve always been political, whereas they’ve always been religious. Those two identities didn’t clash until the rise of Trump’s MAGA, and then I realized there was a part of myself I’d always have to hide if I wanted to keep them in my life. Now, I feel as though no matter how often we talk, they’ll never fully know me since I decided to stifle this definitive piece of my identity that I feel explains so much of who I am. With Scott, it’s something I don’t have to hide. We both agree that we’re cut from the same cloth. My mom doesn’t understand how Scott became the person she is. After all, she grew up in the same place as the rest of our family that we feel are so wildly different from us. But Scott’s the type of person to focus on what unites us rather than what divides us. I didn’t know much about her growing up. I knew she was somewhat estranged from the family after trotting off to New York City in the ‘90s, but I didn’t realize how close we really were until I posted a picture from Kasteel Well on Facebook and got this comment from ‘AS’: “Where are you?? Is that Kasteel Well? Is this the Emerson school?” I responded, “yes it is!” Best to keep it short and sweet, I thought, since I had no clue why this random third cousin would be able to identify my campus from just one picture of naked trees and a moat. But then she responded: “I was a professor at Emerson in the late ‘80s early ‘90s and taught at the Castle in 1993-4. How crazy is that?” That’s when it started. A year and a half later, I thought about the prompt for this semester’s magazine issue-what connects us? I thought about me and this random distant relative who were tied together by a medieval castle owned by Emerson in the Dutch countryside. But it turned out to be so much more. It’s a now-defunct alternative press publication in Boston that Scott was the editor of while getting her master’s in writing, literature, and publishing at Emerson. It’s the first gay-friendly bar in the town that she and my mom grew up in. She said she opened it because there were no other cool places to go, so why not make the cool place? It’s the bar she tended in Boston, where she served the likes of Winona Ryder and Johnny Depp, next to the Four Seasons on Tremont, back when it was the Ritz Carlton. It’s the view of the stars from her farmhouse, which my Aunt Sue says is “the best view of the stars you’ll ever see.” No trees, no lights, no people. Just wide open space and the brilliant night sky. Over a long weekend, in the middle of the fall semester, I asked my mom to take me to see Scott. She wanted to meet at a little coffee shop in Appomattox, about halfway between Richmond (where I’m from) and where my mom grew up. I knocked out during the car ride there and woke up to a sign welcoming travellers to the town “where the nation reunited”-where the Civil War ended. The Blue Ridge Mountains looked true to their name-they gleamed cerulean in the distance. We walked into the coffee shop (she wanted to meet here because it’s owned by “big ol’ libs”). Then I saw her, dressed in all black, wearing dirt caked Hunter boots, with a long black bonnet concealing her dark, curly hair. Just like my mom’s. The first thing I noticed was that she didn’t have the drawling Southern accent that my grandparents, aunts, and uncles all share. The second thing I noticed was that it actually wasn’t gone, just hiding. Waiting ‘til she gets real fired up about something, impassioned, hands flying in the air, inhibitions released. Then, the ends of words start “droppin’.” Just like me. She told me about writing plays at Emerson in Boston and teaching about great female writers at the Castle. She told me about her uncle, the school superintendent of Campbell County who made the decision to integrate the school system during the Civil Rights Movement, only to wake up to a burning cross in his yard. She told me about her mother, the voter registrar who traveled across Appalachian Virginia to attend African American church services and register Black voters. She told me about her family getting death threats from the Ku Klux Klan because of it. For hours, I sat, enamored and fascinated by her very existence. Like me, she worked at a bar through college while simultaneously editing-her at the Boston Phoenix and me at The Beacon. She came back to the place she grew up in to visit her parents, who were both much sicker and older than she expected to find them. She remembers riding in her daddy’s truck to bring the cattle to the market and telling him it’s not just a visit. She was tired of the fast-paced city life and was ready to return to the country for good. “He looked over with tears in his eyes and said, ‘Well that’d be mighty fine,’” she told me, her own eyes glistening too. After our first meeting, we planned a phone call. It was that call where she told me about hammock camping across Central America in the middle of getting her master’s. She spoke of the transcendence she experienced sitting atop Mayan ruins at night, with monkeys and toucans as her roommates. The phosphorescent waters in Mexico, where all the waves break at the same time because of a continental shift causing a mile-deep drop on the ocean floor. She also told me about her home, where she once had to chase out a cooper hawk, where she would drive up the road to get heirloom fruits from trees that were hundreds of years old to make treats and desserts for her friends, the way my great-grandmother Betty did. She also remembers Betty, her aunt, fondly, how she’d come over and bake big cakes, make sweet tea, and stay up all night playing the card game Rook. She remembers how Betty used to pinch her fingers, squint her eyes, and say, “I love you thiiiiis much,” a testament to her humor. I think about how my mom has that phrase tattooed on her arm now. We talked about our family history, the 16 siblings my great grandfather Norris had. How his parents wouldn’t go to his sister’s-Scott’s mother Annie’s-wedding because she was marrying a Methodist man and they were raised Baptist. I think about how upset my grandparents were when my mother told them she’d be marrying an atheist. Not just an atheist, but a Northern one too. Bless her heart. I think about how despondent they’d be if I were to marry a woman. I’m certain they’d never speak to me again. They certainly wouldn’t attend the wedding, and my grandfather would die before officiating it-which I grew up my whole life hearing he wanted to do. I think about how he became the bitter man he is, damned to spend the rest of his life in a wheelchair due to exposure from Agent Orange, a highly toxic herbicide, in Vietnam. I remember how Scott told me my great-grandfather Norris died from asbestos exposure in the Navy. How my dad was exposed to that, too. How those three men have all reconciled differently with the cards they’d been dealt. And my mom, who returned to Lynchburg, Va. for the first time in probably over a decade to see her father in the hospital. He sneered when he heard we visited Scott. How could someone who had traveled the whole world and lived in some of the biggest cities on the East Coast decide to come back to a small mountain town in Virginia despite it all? For the same reason she opened that little gay bar, where she told me Venezuelan baseball players came to dance with lesbians. Where the drummer of The Psychedelic Furs came to perform-a scene straight out of her groovy stomping grounds in Brooklyn and Back Bay. Because people like us still exist in places like that little mountain town in Virginia, even if you don’t see us. Upon moving back to Virginia in the late ‘90s, Scott decided to open up her bar because her and her friends didn’t have anywhere cool to go for drinks and dancing. Lo and behold, there was a whole sleeper cell population of “freaks,” as Scott affectionately calls them, waiting for a safe space to come show themselves. In a town like Lynchburg, home to Jerry Falwell and Liberty University, that act is more than brave; it’s revolutionary. And it’s necessary, because queer people are everywhere. Even in the mountains of Virginia. This existence is more of an act of courage than being who you are in any of those other places that welcome you with open arms. That’s what Scott embodies-embracing who you are loudly and proudly for the chance of finding others like you, despite the guarantee of hatred, discrimination, anger, and even danger. Accepting that those things shape you just as much as the good stuff. It’s a lesson I learned on my own, as Scott did too. And her mother before her. And her mother before her.

https://berkeleybeacon.com/the-outlaw-of-appalachia/